“All is flux” – Heraclitus of Ephesus

We’ve focused on three things since the onset of COVID-19: the pandemic, its economic fallout, and the market’s discounting of shifting prospects. As the economy and markets were heavily influenced by the uncertain path of pandemic and related policy responses, the virus was our initial focus. Today, health uncertainties remain but have moderated, eclipsed by new concerns about inflation.

Since our last comment as of 3/31, seven-day average new cases of the virus in the US declined 81% and deaths fell by 73%. Since their respective January peaks, average new cases have fallen 95% while deaths are down 92%. We’re not out of the woods yet: most of the world lags the US in vaccine administration (prime exceptions being Israel and the UK), and new strains such as the possibly more vaccine-resistant Delta variant could derail pandemic recovery. But trends are good and expected to continue.

As to the economy, in the first quarter, GDP essentially recovered to pre-COVID highs, so the recovery has now become an expansion, and a boom expansion at that, even if wildly uneven. For example, from pre-pandemic levels in February 2020, non-farm payrolls were down 5% through May 2021 while retail sales were up 12.9%, both highly impacted by massive transfer payments from the federal government. This also illustrates strong growth in productivity which is unambiguously good.

US unemployment went from 3.5% in Feb 2020 to 14.8% in April, then quickly declined to 10.32% by July and 6.7% by year-end. From there it improved more slowly to 5.8% in May, the latest data. There are now 9.3 million open and unfilled jobs in the US – about as many as there are unemployed persons and perhaps mostly reflecting a mismatch in skills desired and available.

Economic recovery was accelerated by government largesse which in turn was accommodated by federal government borrowing and Federal Reserve money creation (that is, buying mostly government bonds in the “open market”). Over the past 15 months, our country’s national debt has increased by $5 Trillion (21%) while the Federal Reserve’s “balance sheet” expanded by $3.5 Trillion (92%).

With last year’s lockdown requirements, production was steeply curtailed, so demand for many goods used in production declined abruptly and their prices fell precipitously – recall our commentary a year ago when crude oil futures prices briefly went negative. Later, initial reopening coupled with additional government stimulus and very easy monetary policies from the Federal Reserve set the stage for shortages in a wide variety of items and recoveries in prices that had fallen last Spring. This caused strong year-over-year commodity price growth which flowed into the inflation measures. Of concern now is that the CPI has not only recovered to its former trend-line but has overshot. US consumer inflation in May was up 5% year-over-year – higher than all but three such readings in the past 30 years.

That inflation turned up significantly was no surprise. The question is whether higher inflation will be transitory or persistent. Commodity price comparisons and supply chain bottlenecks argue it’s a temporary phenomenon. But with worker shortages and the most recent reading of average hourly earnings climbing 6.4% since February 2020, wages may be trending higher too. Unlike fickle commodity prices, wages are “stickier”. Moreover, some portion of inflation is a function of expectations, which can assume a life independent of the economics.

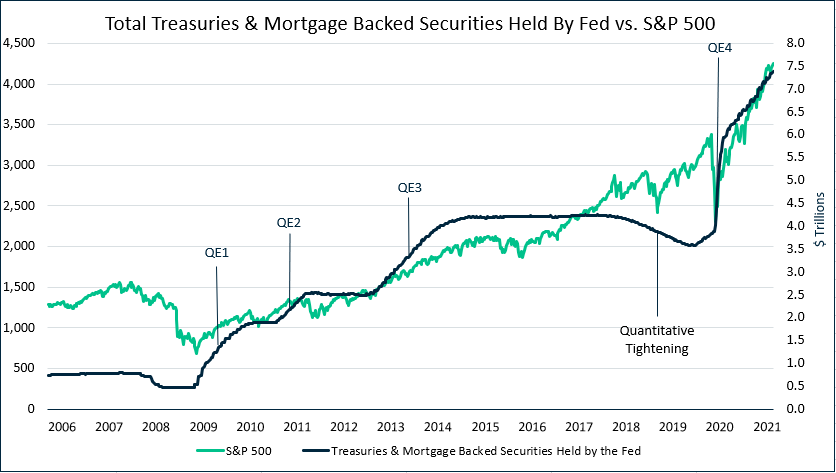

We suspect most current inflation might prove temporary, while some may be more persistent, but we don’t know. We’ll have to see. What we do know is this is the most urgent unanswered investment question of the hour (and number two and possibly number three as well). The reason is any moderation in accommodative Federal Reserve policy will be dictated by future inflation, Fed policy in turn defines liquidity, and liquidity drives markets in the short to intermediate run. Consider the obvious correlation between the US stock market and the size of the Federal Reserve’s “balance sheet” since 2008:

Source: Federal Reserve Economic Data, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

For now, earnings expectations are rapidly rising for most stocks while interest rates remain very low – a positive combination for stocks. But investors must prepare for eventual storms as well given recent strength in inflation and comments from the Federal Reserve. Concurrent with its June meeting, the Fed raised its inflation projection from 2.5% to 3.5%, projected a hike in interest rates in 2023 rather than in 2024, and expressed surprise at the speed of US economic recovery and concern at the sharp gains in commodity prices.

Regardless of short-term swings in expectations, investors can step back and realize the Fed is holding short-term interest rates near zero while buying $120 billion in bonds each month as if the US were still in a financial crisis - such an accommodative Fed won’t persist forever. In the long run, stock earnings can be somewhat protected against inflation when companies can pass on increased costs through higher prices. But the current lofty valuations investors place on those earnings will likely shrink in an environment of higher interest rates. Therefore, long-term return expectations must be tempered for stocks.

Bonds in a low interest rate and rising inflation environment are even more problematic. When rates are low and inflation is also low, bonds might simply offer very low but positive “real” returns after inflation. When rates are low and inflation is higher, bonds become even less attractive, potentially offering negative “real” returns after subtracting inflation. In the face of low rates, we’ve generally maintained shorter bond maturities. In addition, we’ve lately expanded short-term “Alternative Lending” holdings in our managed bond portfolios: insurance-linked bonds, direct corporate lending, non-bank commercial mortgage lending, and private fixed income where appropriate.

A blended stock index of 70% US and 30% international stocks (to which we compare global equities) returned 13.3% in just the first half of the year. That follows a strong market recovery last year after a sharp market sell-off in the Spring. Large moves such as these result in portfolios becoming overweight in stocks, requiring portfolio rebalancing. In doing so, we increasingly encounter tax constraints. As we balance the costs of capital gain realization against the extra risk associated with portfolios overweight to stocks, often the compromise is a combination of somewhat higher capital gains than normal this year and somewhat greater portfolio risk until next year when some deferred stock sales to rebalance portfolios might occur. As an additional complication, now come efforts to raise capital gains taxes, which if passed would require additional adjustments.

Life is flux, and so are markets, but seldom more so, it seems, than when overlaid by a pandemic. Sticking with a solid plan is essential when the winds shift strongly and quickly. In hindsight, buying stocks to rebalance portfolios to target allocations during last year’s sharp and quick bear market has been very fruitful. So has staying with a disciplined, value-oriented investment approach during the period when that also suffered a bear market in relative returns. Discipline to do both then has paid off well now. Today, we will do well to also recall rebalancing works both ways and that we are entering a period in which disciplined risk control in the face of market strength can be as important now as buying into market weakness was last year.